One of the most well known horror novels in history is that grim jewel, Dracula. Yet even as I read it, I could not help but ask: what is horror and what is fantasy? These two are often treated as opposite kingdoms, light against shadow, fairy tale against nightmare. But the truth is they are the head and tail of the same coin, minted in the furnace of enchantment. Both are born of mystery, both thrive on the unknown. And if fantasy invites us to wish, horror reminds us that our wishes may not always be safe.

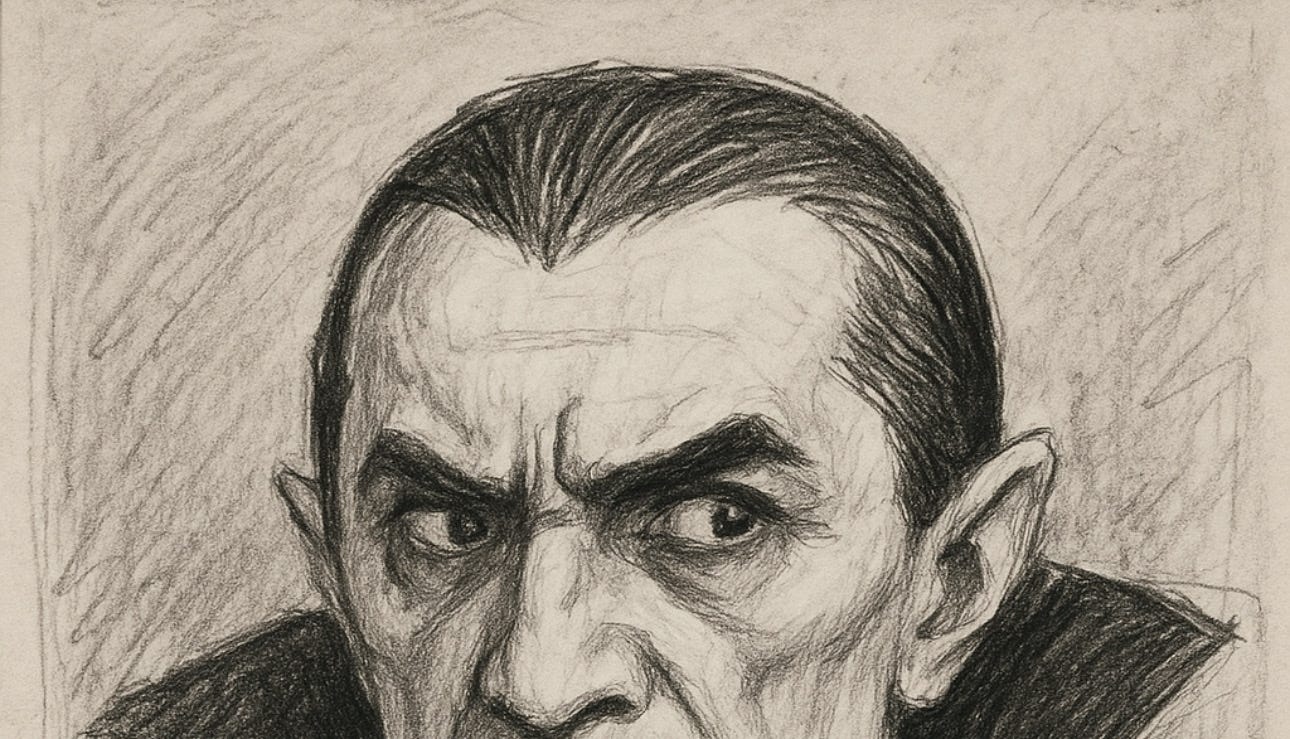

What first struck me was not the terror, but the gentleness. Van Helsing, in popular imagination, has become a grim caricature, a cold arrogant tactician obsessed with ridding the world of vampires. Pop culture paints him with the same brush as the monsters he hunts. But Bram Stoker’s Van Helsing is something altogether different. He is, in fact, a gentleman of all gentlemen, “full of pity and tenderness” as one character describes him, a man who could as easily sit with you in a study, sipping brandy and reciting poetry, as he could stake a vampire. Consider how he is described in friendship:

“He is so sweet and sympathetic and so full of a fine sense of humour that I feel that I am in friendship with him already. He has a noble nature. He is so tolerant and patient and kind that I feel as if he were my own father.”

At another point Van Helsing shows his gentleness in grief. When Lucy dies, he comforts the mourning men, his words almost pastoral:

“She is one of God’s women, fashioned by His own hand to show us men and other women that there is a heaven where we can enter, and that its light can be here on earth. So true, so sweet, so noble, so little an egoist, and that, we men who are selfish, can hardly believe such a one to have been.”

This is not the voice of arrogance but of gentleness. Not the tone of obsession, but of wisdom.

And it is curious, perhaps even ironic, that our culture has inverted the symbols. Vampires are romanticized into daydreams, handsome immortals who glitter in sunlight, while Van Helsings are cast as narrow fanatical monsters. In the turning of the tale, the hero has been made the villain, and the villain a lover. That is itself a horror worth noting.

Yet the most fascinating element of Dracula is not its characters but its conception of horror itself. What terrified the band of companions was not first the teeth or the blood, but the lack of sense that lay over everything. Horror came as incomprehensibility.

A sickness with no cause. Pale faces and marks on the throat. Strange happenings in the night. Empty graves. And, most chilling of all, the sight of the lovely Lucy transformed, once the image of innocence, now a predator thirsting for her own husband’s blood.

There is a powerful exchange between Dr. Seward and Van Helsing that captures this tension between sense and mystery. Seward, the man of science, cannot bring himself to believe. Van Helsing presses him:

“Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are? That some people see things that others cannot? But there are things old and new which must not be contemplated by men because they know, or think they know, some things which other men have told them. It is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all. And if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain. But yet we see around us every day the growth of new beliefs which are of the same nature of old, and which are yet passing strange.”

This is the heart of horror, the recognition that reality itself is stranger than reason can contain. It is not the absence of meaning, but the presence of meaning too large for our nets.

We flatter ourselves by calling fantasy wishful thinking and horror the sober account of the bleak. But both are wishful. It is as wishful to say evil will endure forever as it is to say good will triumph in the end. We are mistaken when we imagine that dark dreams are somehow truer reflections of the world than bright ones. Stoker’s tale reminds us that mystery cuts both ways. It is frightening to realize there are realities we cannot comprehend, especially when they endanger us. But it is equally exhilarating to imagine that those mysteries might be for our good.

At one point in the novel Van Helsing confesses the limits of his own field, and in doing so, he opens a window into something much larger:

“Ah, it is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all. And if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain. Yet we see around us every day the growth of new beliefs which are of the same nature of old, and which are yet passing strange.”

There are more things in heaven and earth,” said Hamlet, “than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Dracula whispers the same. There are millions of things science can never solve, and our peril lies in pretending otherwise. The great choice before us is whether we will be horrified by mystery or enchanted by it.

In the end, Dracula leaves us trembling not merely at vampires, but at the abyss of the unknown. Yet perhaps the very abyss that terrifies us can also enchant us. For the dark tunnel of mystery, if we walk far enough, may open at last into light.

There is a difference between good and evil, and between reality and fantasy. The difference between horror and fantasy, though, may not be as simple as light and dark. Perhaps it rests in how mystery meets us, sometimes it terrifies, sometimes it enchants.